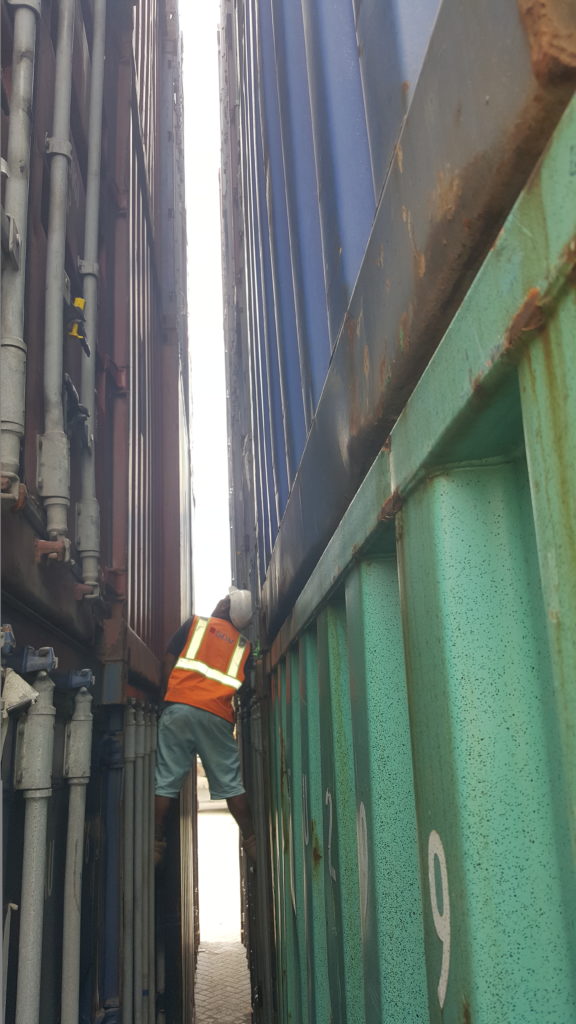

It’s pushing 40⁰ C, the sun is blazing, and it feels like the air is holding more humidity than is physically possible; like the slightest disturbance, a loud sneeze or a backfire, will begin an epic, biblical deluge. I’m sandwiched in an impossibly small, claustrophobic space, squinting through the glare of the sun and the sweat dripping in my eyes, trying to read the numbers printed on the walls of shipping containers on either side of me. Above me, a small, bearded Timorese man dressed in a high-viz jacket and heavy steel-capped boots is trying desperately not to kick me in the face as he shimmies up between containers to read the numbers we cannot see from the ground. After a few minutes of grunting and cursing, he returns. “It’s not here, I don’t know.” he says, defeated. We retreat to the shade to, once again, examine the ship’s manifest and double check, for the hundredth time, the number of the container we are looking for. It’s not looking good.

We were always expecting some delays in getting our car off the ship from Darwin and arriving amongst the Christmas and New Years’ holidays may have been tempting fate. We arrived in Dili on a Sunday but had allowed a whole week to deal with the bureaucracy of getting our car back and organising our Indonesian visas. In theory, retrieving our car from the port should have been a relatively straightforward affair. A customs official signs and stamps the Carnet de Passages en Douane (which allows for the temporary importation of a vehicle without having to pay import duty), we present the Carnet to the shipping agent who provides us with a Bill of Landing, which we return to customs, who can then break the seal on the container and confirm that the goods inside are correct. We should then be free to drive our car out of the container and onwards to wherever we want to go. There are a couple of pretty critical assumptions being made in this equation; firstly, that the customs officials know how to correctly fill in the Carnet, and, secondly, the container is where it is supposed to be.

We loaded our car into a container in Darwin.

Monday morning, I struck out to Dili port and after a few false turns, I found some very helpful customs officers who spoke exactly three words of English between them. I mimed and gesticulated what I needed; they smiled and nodded but looked very confused. Eventually one of them realised what I wanted and ran off to get some forms which would have been correct had I been the master of a cargo vessel wanting to dock in Dili port. I explained that I did not, in fact, have a cargo ship in my possession and all I needed were some signatures and stamps on my Carnet. Clearly the first assumption had not been met; neither of these officials had ever seen one before and had no idea what it was. After a lot of pointing and nervous laughing, we managed to get the Carnet signed and stamped in all the right places.

Next stop, the shipping agent. After the success with customs officials I was feeling buoyant and took my time wandering the few blocks to the shipping agent’s office. I arrived at a suspiciously dark and empty office, a lone dog barking through the gate and a security guard sleeping on the steps. With my mood sinking, I walked in, presented my Carnet to the guy at the front counter and told him I was there to get my car. “Sorry“ he said apologetically, “there’s no one here today. It’s Holiday.” What?!? The government officials at the port were working! The following day was New Year’s Day so that was a holiday too. “Can I come on Wednesday?” I asked the guy. “No, also holiday, Maybe Thursday?”. I had no option but to wait.

Thursday broke hot and humid. I walked along Dili’s waterfront to the chorus of bizzarely decorated taxis honking, looking for a fare, past road side vendors selling fruit and cool drinks out of little carts, walls covered with obscure political street art, statues depicting Timor Leste’s struggle for independence and clocks which were all utterly wrong. I arrived at an open office, where it genuinely appeared that most staff were employed simply to staple bits of paper together. I presented my paperwork at the front counter, fully expecting to be taken to my container. After being slowly ushered from desk to desk and being given numerous pieces of paperwork, none of which were mine, I was finally given the correct Bill of Landing and told that everything was in order. But just as I walked out the door a man called me back. “Excuse me, wait, wait!” he called “The customs regulations in Timor have changed. Take this form back to customs and they will enter the details into their computer, then open your container and check that your goods are correct”. Ok, fine. I knew where the customs office was and felt confident that I could mime my way through this too.

I walked to the port and back into the customs office to see the same smiling faces who signed my Carnet. I explained that apparently, there was a new process which I had to follow, but it seemed they were unaware there was a process, let alone that it had changed. Eventually they called the shipping agent who sent Mr. Moises to help. After a brief, seemingly hostile, consultation, everyone fled the room. I was left holding all my paperwork with absolutely no clue as to what had just transpired, or what was happening next. I waited for 10 minutes and Moises returned. “No problem, I find your container and customs will open. Come back in 20 minutes”.

I returned to the customs office and found Moises a little flustered. “I’m not sure where it is, I keep looking.” He said. “Ummm, OK.” I said with a twinge of concern. I followed him into the yard where started a mad search for my container, my little friend conscripting worker after worker until we seemingly had half the port workmen in our gang, all scouring row after row of containers stacked three or four high; and four deep. Men scaling the sides of the walls to peer down at the labels from above; all of us searching high and low for an oversized needle in a giant’s haystack. After two hours, Moises, exhausted and sweating, approached me with a look of panic. “We stop now. Lunch. You come back at two o’clock, we look again after lunch.” The second assumption in the equation was starting to look pretty shaky too.

Mr. Moises scales shimmies up between containers to read the numbers not visible from the ground

By mid-afternoon it was sweltering; the air thick with humidity. I returned to the port, found Moises and his band of workers, and we continued the mad, chaotic search. Someone had produced a few copies of the ship’s manifest so all could be certain of what we were looking for. By close of business, I had been reduced to nothing more than a barely sentient puddle of sweat but we were no closer to finding my container. Moises apologised profusely but there was nothing more to be done until the next day.

I arrived back at the port early and found Moises already leading a desperate search. Again, he had enlisted a small Timorese army of workers to search over the containers we had searched the previous day. A crane had joined our party and was shifting containers, seemingly at random, so the men could look more closely at those that were buried. Lunch time arrived and still no sign of my container. “No container, I don’t know where it is.” Moises despaired “It must be here. It came off the ship.” “Does this happen often?” I asked, defeated. “Not much, but sometimes.” He replied. “I keep looking.”

I spent an increasingly desperate afternoon back at the office of the shipping agents speaking to anyone who would listen and getting bumped around from person to person, none of whom could shed any light on the whereabouts of my container. While I was waiting to speak to the branch manager, a man behind the front desk looked up from his stapling and casually suggested that I speak to the ship owners. What?!? For two whole days we have been searching hundreds and hundreds of containers and no one thought to check with the owners of the ship? At my wit’s end, I caught a taxi across town to the office of the ship owners and spoke to a very professional receptionist who said she would ask around and see if anyone knew anything. I left my contact details, but this being late Friday afternoon, I was not hopeful. I left the office dejected and angry and returned to our hotel.

Rows and rows of containers in Dili port. We searched every single one, more than once…

The next morning, I was astounded to see an email from the receptionist. “I spoke to the captain of the ship. He looked and your container is still there, it was never unloaded. It goes now to Singapore.” Our container had been incorrectly loaded in Darwin and was now completing the Dili-Singapore-Darwin-Dili circuit without us. After a few more emails we were assured that the container was safe and would not be accidentally unloaded at any other port. There was nothing left to do but wait. Welcome to Timor Leste!

P.S.

Our container took another 23 days to complete the circuit. When it finally arrived, I went to the port, signed in as a visitor (which I had not done on any of my previous visits), was given a hard hat and promptly taken to my container where it was opened by customs and I was allowed to drive out. I eased the car from the container, put my foot to the floor, and drove from the port. I didn’t return the hard hat.